17 Aug Investigative Journalism Piece by Louis Chant

Is it easier for musicians to distribute their music, compared to the past?

In this current economic climate, more and more musicians are seeking to release their music independently, instead of applying for a deal through a major label. Musicians for decades have released their music through record deals on major labels, but this has changed over the years after the invention of websites and services such as SoundCloud and Bandcamp. Speaking to two different musicians in a similar field, we find out how easy is it to distribute your music nowadays, and how does it affect certain musicians of certain calibers?

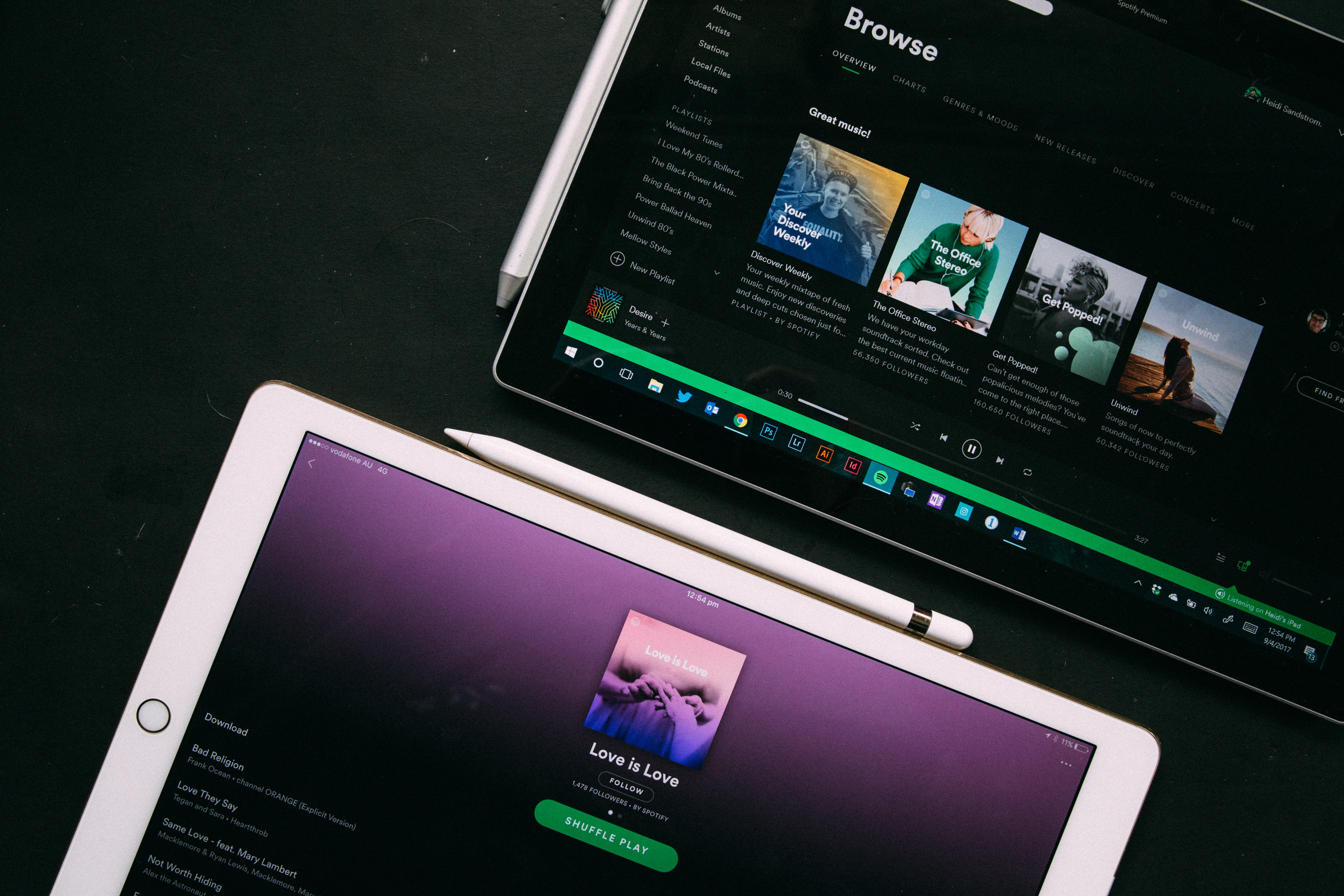

Washington D.C-based musician Andy Hoang, is a musical producer who makes disco-electronic music under the alias of ‘Discoholic’ with the guise of a giant disco ball being his gimmick and alter-ego. He has also been making songs with different aliases for nearly three years now. With the power of the current-day Internet, Andy has been able to release his music under a ‘net-label’, which is essentially a record label but only solely releasing digital formats of records like the .mp3 or .wav. The net-label “Montaime” is a project that both Andy and his friend Romanian-born but Baltimore-based musician Alexandru Galetus (also known as FIBRE Music) work on, releasing their own music and DJ mixes to platforms such as SoundCloud, Spotify and more. The label pulls in talent from across the globe, reaching as far as London, to even the deepest stretches of Japan.

Because of the current social and musical landscape that’s offered to smaller musicians nowadays, more and more people can distribute their music to their audiences and the general public compared to the distant past. Andy can easily upload his song to SoundCloud and his audience can listen almost instantaneously. Musicians in the 70s/80s had to release their music via vinyl disc, or promote their tracks to a good enough standard to even stand a chance to launch themselves onto television or radio. The technology of nowadays cuts out the middleman and gives the musicians of today a chance to finally live their dreams as a bonafide artist, whether or not their music gets a hundred plays or a hundred million.

Each streaming platform pays out a certain amount per stream. This can wildly differ, and you’ll find that the smaller platforms that garner less customers pay out more than the bigger corporations. According to an article published back in 2018 by CNBC, Spotify pays out roughly 0.006 dollars a stream. If your song reached 100,000 streams, you’d be looking at a 600 dollar pay-check. However, this is only if you released your song independently, most of the time a major label would probably take a cut of whatever you earn and keep it for themselves in return of promoting your music and distributing it themselves. Apple Music on the other hand pay out 0.00735 dollars a stream, only slightly higher than Spotify but still beneficial if your streams hit the big numbers. A service that most people have seen to have forgotten about, aka Napster, pays out a whopping 2 American cents per stream. So if your song was streamed 100,000 times on their service, you’d earn 2000 dollars. That’s enough money to make a living off streaming alone if you’re a musician, but sadly less and less people use Napster as the days go by.

The experience as a whole on a platform such as YouTube is completely different, however. You can be paid for your streams via Adsense monetisation, but most smaller musicians often go down the route of getting their music on a promotion channel that will host their music as a form of free advertising, or paid gig. One channel that stands out amongst the others is Artzie Music, a channel boasting over 347,000 subscribers. Their trademark videos of Anime/Colourful backgrounds with the Disco/Funk influenced music racks up lots of views. In recent times however, Artzie have had to change up their video-based formula, due to copyright strikes from the copyright holders of the looping videos in the background. They now create their own backgrounds from scratch, and because of this, their viewership is slightly lower than it used to be. Owner of Artzie Music, Breezy Riley, said that “Although we’ve changed our visual look, we feel like people have no point in unfollowing us, simply because it’s all about the music in the end, isn’t it?”

Another way of getting lots of streams nowadays is via specifically made Spotify playlists, that tap into certain markets with their selection of music. Say for example you’re a big corporate label and you create a playlist with solely hip-hop music on, you could pay a small fee and get your track hosted on their playlist, which usually attracts a lot of people to listen to music on there. This is a tried and tested formula, however, some people are against it, simply because it’s somewhat ‘manipulating’ the music industry.

I wanted to get a veterans perspective on the streaming world and what they thought about it, so I enlisted the help of Daedelus, a Los Angeles-based producer who’s released music on a whole host of labels such as Flying Lotus’ “BRAINFEEDER” and collaborated with the likes of MF DOOM and Machinedrum. Daedelus has been releasing IDM/Electronic music for over 20 years now and has seen the musical landscape change and transcend. Speaking via email, he said that “Before the disruption of file services like Napster (and those that followed) there seemed an impossible task of releasing music. Quite simply gatekeeping by labels was strong, and direct sales of physical formats was viable, you didn’t really exist unless you were on shelves. Mind you the lion share was in CDs and Majors had a strangle -hold on production of the format. Making matters worse was the media was also quite beholden to the largess of labels, so hard pressed to get any attention/articles about unless the stars aligned. I personally had a tough time finding interest in marginal/experimental electronic styles in the early 00s.”

What’s interesting is, later on in the paragraph he speaks of a time where in “2005 to 2017, you couldn’t really say who was in charge of distribution” essentially entailing that the music industry was a no-man’s-land, and anyone could seize control of it. This was in the heyday of Myspace and early Facebook mind you, and blogs ruled the internet. Nowadays major labels have quite a large control over the distribution of music, but services such as Bandcamp allow lone musicians and bands to do this on a smaller-scale, at least.

On a smaller tangent, Alfred says “All this isn’t to say that traditional get-in-front-of-ears promotion are any less effective. Music is central to identity and culture. I believe consumers are more sophisticated than ever and crave authentic (or at least outrageous) embodiment’s.” In a way, his closing statement suggests that people are still longing for more authentic ways to listen to music, whether that’s still through CDs or Vinyl. Vinyl is currently selling at an all-time high, and even Cassettes are on the rise sales-wise. Unfortunately, it seems like streaming will be the main way people listen to music now, for a very long time.

After all this research, we can positively say that it is easier to distribute music in the current day, compared to the past. The future is always uncertain – so who knows what we may see?