17 May How Psychedelics can heal our brains, and still land us behind bars

An investigation into the current climate around psychedelic research and legalisation.

The UK is currently in the middle of a mental health crisis. Figures from the Beckley Foundation show that 1 in 4 people in the UK are affected by mental illness, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) deeming depression as the leading cause of disability globally.

In a report by James Lake, MD, published by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information, he explains: “Existing models of care and available treatment approaches fail to adequately address the global crisis of mental health care”. He continues: “Despite the increased availability of antidepressants during the past few decades, limited efficacy, safety issues, and high treatment costs have resulted in an enormous unmet need for treatment of depressed mood”

This past decade, prescriptions of SSRIs and other serotonin inhibitors to treat depressive and anxiety disorders have doubled. The NCBI estimate that up to 35% of people who are prescribed this form of medication will see no benefit to their mental health, with 15% of those going on to take their own lives.

Since the discovery of these drugs, there has been no major breakthrough in the pharmaceutical treatment of depression and other psychological disorders in over 3 decades. The current system is failing and with rates of depression rising faster than any other health condition, our society desperately needs new solutions.

Groundbreaking developments in the field of neuropsychopharmacology suggest that these solutions may have been under our noses for decades, kept from us by misinformed legislation and public stigma.

Research over the past two decades on psychedelics have found that the use of these substances, coupled with psychotherapy, produce dramatically higher rates of efficacy than any other treatment currently available. The positive impacts of these substance are immediately clear after even a single dosing, with the recorded benefits to a subjects mental state lasting weeks, months and potentially years.

A massive positive in favour of the use of these treatments is the absence of any recorded negative short or long term side effects, a considerable factor when looking at the plethora of adverse health effects that the use of SSRIs can be responsible for. Harms linked to the use of seretonin inhibitors can include decreased alertness, loss in sexual function, diabetes, hypomania and can even result in thoughts of suicide and self harm.

Research at Imperial College London and Kings College London is spearheading these developments. The Beckley/Imperial Research Program was founded in 2008, led by Amanda Fielding; an English drug policy reformer and founder of the Beckley Foundation (previously known as the Foundation to Further Consciousness), alongside David Nutt; former chairman of the ACMD (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs) and current chair of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College.

The program is responsible for some of the most groundbreaking research into the effects of psychedelics on the brain, creating the worlds first brain imaging study of LSD and piloting a highly successful clinical trial into the therapeutic effects of psilocybin on treatment resistant depression.

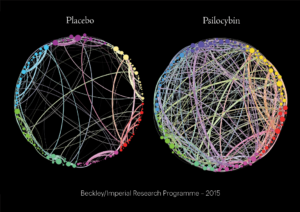

Dr James Rucker is the Senior Clinical Lecturer at Kings College London and is leading their psychedelic research team. When asked to detail the neurological processes behind the treatment, he explained: “What we know is, these drugs seem to de-constrain tightly regulated networks of brain activity. We relate this clinically to ‘old habits die hard’”.

Under the influence of Psilocybin, our brain regions communicate much more frequently with other neural networks

“Once you’ve learnt to be depressed or anxious, its hard to get out of that rut. That’s partly because these patterns of neural activity are biologically habituated. The idea behind the treatment is, by relaxing those patterns, you create a window of opportunity in which to foster salutary change.”

“We need something which works in a different way, and it seems that psychedelics do just that”.

The use of psychedelics in the practice of psychotherapy is nothing new however. LSD was first synthesised in 1943 by a Swiss chemist named Albert Hofmann, who first discovered the psychoactive properties of a drug he had labelled LSD-25 after accidentally dosing himself. His employers then began to sell the drug to doctors and researchers, marketing it as a tool to better understand psychosis and to aid in the practice of psychotherapy.

In the years following Hofmann’s synthesis, over 1,000 scientific papers were published on LSD therapy, with over 40,000 patients being administered the drug in clinical trials. This is widely referred to as the ‘golden age’ of psychedelic research.

Although Hofmann’s work marked the beginning of the utilisation of psychedelics in modern medicine, their use throughout history is well documented. Archaeological discoveries in the US have yielded peyote (mescaline) specimens, found in the context suggesting its ceremonial use over 5,500 years ago. The drug, produced by the peyote cactus native to Mexico and southwestern Texas was used by Native North Americans both medicinally and ritualistically, referring to it as “the sacred medicine”.

By the 1960s, these drugs had escaped the laboratories and began to be widely used recreationally by millions of baby boomers, fuelling the counter-cultural, anti corporation, anti war movements that immortalised the 60s as a decade of social revolution across the Western world. Timothy Leary, a Harvard University psychologist and psychedelic advocate was deemed by President Richard Nixon as “the most dangerous man in America” for his role in promoting the use of these drugs as a spiritual liberation.

The untapped utility of these drugs were not overlooked by the US government, who instead carried out experimentation of their application as a tool of war. Project MKUltra, now commonly referred to as the CIA mind control program, was the code name given to a series of experiments on human subjects in an effort to develop methods of weakening the individual and force confessions through mind control. The project, often illegally, used US and Canadian citizens as unwitting test subjects; dosing them with large amounts of LSD and other chemicals and subjecting them to sensory deprivation, hypnosis and torture. The operation was sanctioned in 1953 and was recorded to be fully halted in 1973.

Before 1965, LSD’s presence in the UK existed solely within the hands of psychiatrists and military scientists. However, the year saw the sudden widespread public use of the drug, sparking dramatic changes in British culture akin to the movements in the States. The following year, the drug had came to the attention of the government after its use was linked to multiple cases of poor mental health, accidental deaths and suicides. In 1966 the recreational use of the drug was made illegal.

Psilocybe mushrooms (magic mushrooms), Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and other similar psychoactive substances currently hold a Class A drug rating in the UK, a classification that they have held for over 40 years since the controversial Misuse of Drugs Act (1971) was put into effect.

The current penalties for the possession of these substances is a prison sentence of up to 7 years with an unlimited fine, with the punishment for the production and supply being a potential life sentence.

When asked why research was beginning to gain momentum globally, Dr Rucker explained: “I think its a combination of the research and very subtle change in attitudes to drugs. In the medical profession, there is a despair about the treatments that we’ve currently got; although they help some people, there’s a large portion that they don’t and for some people it seems to make them worse”.

“I was brought up in the 80’s and 90’s with the drug war in full swing. Drugs were the ‘bad guy’, unless they were prescribed by a doctor. But of course, drugs aren’t good or bad. They are just tools, and with any tool you have to figure out how to use it.”

This sentiment seems to be echoing across the western world. In a historic vote, on May the 8th, Denver because the first city in the US to decriminalise the use and possession of psilocybin containing mushrooms. Although the drug still remains illegal under state and federal law, Initiative 301 prohibits the city from spending resources to pursue criminal penalties for possession by those aged 21 and above.

Regardless of the wealth of scientific evidence disproving the negative attributes given to these drugs, the UK government remains firm on its claim that psychoactive substances are scheduled based on their harm. These assertions seem to be baseless, as the House of Commons’ own Science and Technology committee have described UK drug law as “unscientific”, “arbitrary” and “based on historical assumptions, not scientific assessment”.

Public perception of psychedelics is rapidly changing however, credited to the dedicated work of scientists and researchers both in the UK and overseas. With our knowledge and understanding of these drugs and how they can alter our minds ever expanding, it seems inevitable that Governments will be unable to ignore the facts for much longer.

The future looks bright for psychedelic research, and even brighter for those that it could set on the road to recovery.