13 May Female Genital Mutilation: A Growing Concern In The UK

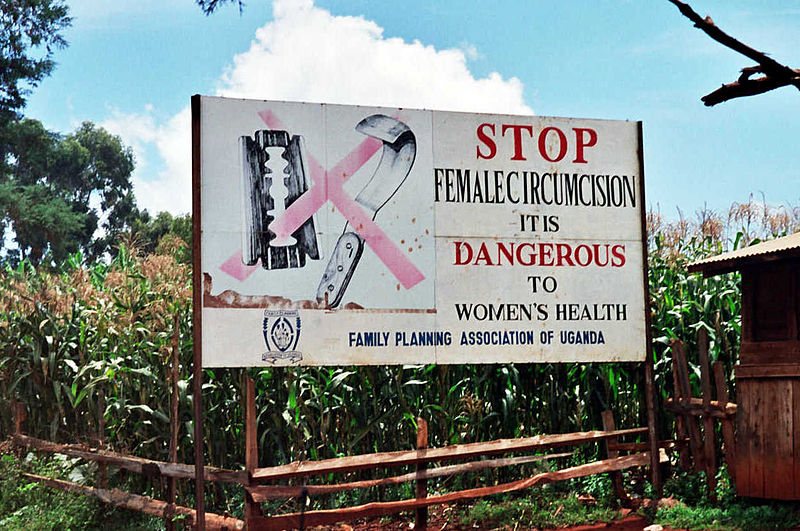

Carried out in females globally from just as young as 4, female genital mutilation; otherwise known as FGM, is a ‘traditional’ practice that is carried out in most countries across the world on a surprisingly large scale. Three million girls and women are estimated at risk each year. The practise includes removing the external genitalia of girls and young women for non medical reasoning. It is illegal in many countries, one of them being here, in the UK, but that doesn’t stop it from being carried out behind closed doors.

An investigation has been carried out in order to expose what happens here in the UK and the global and cultural link and impact this has on young girls today.

Imagine yourself when you were younger, think of the childhood you had and compare it to a young female in Egypt or Gambia, around the beautiful Saharan Horn Of Africa, experiencing female genital mutilation. In 2013 alone, Egypt has the highest total number of women that have subliminally undergone the procedure at 27.2 million women.

The effects of FGM aren’t just physical but long term problems are also there, but they’re never taken into account by the ‘doctors’ carrying this out. These said ‘doctors’ are traditional circumcisers who have no medical training and do not put their patient under any sort of anaesthesia. No professional medical measures are taken after, like prescribing antiseptics. The objects used to carry out the operation can range from glass to unsanitised knives, causing damage to the highly sensitive genital tissue. Child birth also becomes a major concern as the removal of the genitalia makes it extremely painful in having children in the future. Sexual intercourse is also limited as you’re in excruciating pain and have an inability to orgasm.

Twenty eight countries worldwide have FGM being practised in them right this second. However, twenty two of these countries have this act classified as illegal, the remaining six do not have a law banning female genital mutilation meaning that it is still very well legal. The reasons for FGM lie under the fantasy of virginity and sex before marriage. Though no religious texts evoke this practice, it’s still being carried out for sexual suppression of females.

Female genital mutilation was outlawed in the UK in 1985 under the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act. The 2003 Female Genital Mutilation Act made it an offence to perform FGM whether it happened in this country or not. The first prosecution of female genital mutilation took place in 2015 against a doctor, however he was found not guilty. Four years later, the first sentencing happened in February of 2019.

The Ugandan born mother mutilated her three year old daughter. The thirty seven year old coached her daughter to lie about the procedure but authorities later found out when they searched the woman’s home and found evidence of witchcraft. The ‘spells’ were there to deter the police from finding out.

FGM Campaigner Aneeta Prem from Freedom Charity said ‘people are scared to come forward.’

This act has unbolted doors for victims to now come forward about their cases and experiences with female genital mutilation. This then brings me onto Farah Selim, an Egyptian born 18 year old who has been living in the UK for 16 years. Her parents migrated from Aswan, Egypt when she was just 2. What you’ll hear next will shake you.

Her earliest memories consist of running around Nady Degla park in Cairo with her little sister. The memory that comes after happened when she was just 5 years old. It was the summer holidays and Farah’s family went back to Egypt to see family over the school break. She describes her mum driving on the longest road that felt like forever. “I saw palm trees and the beach as my mum drove up the heated motorway, I remember us laughing and joking around and planning what to eat… but she was actually driving me to the worst day of my life.’ The juxtaposition of laughter and hatred comes shortly after.

She sees a young woman rolling a hospital bed into a worn out lime scale infested building the size of a 3 bedroom flat. She questions her mum as to what they’re doing here. Her mum simply replies in Arabic, translating into ‘I’m doing a good deed, that you’ll later thank me over in the future, don’t ask questions just be patient and you will see, don’t be scared.’

Farah has never seen her mum so serious. She knew something was up. The same woman that she saw previously approached her and gave her some Egyptian candy as she saw the worry in young Farah’s eyes. She thought the lady was sweet, but later figured out different.

Her mum accompanied her as they escort the both of them into one of the rooms. I asked Farah if she remembers how she felt in this moment, as the woman she trusted the most was about to betray her. She said “Looking back at it I was naive and confused, I knew what was going to happen next was not going to be what i expected, I remember looking around and seeing used tissues and sharp objects scattered around the small space.”

What happens next changed her life forever. She remembers being in agonising pain and extreme sadness. She then described how life was different after, what changed on her journey?

“I can’t really explain the feeling, I can’t really put into words how much this changed my life and as I got older, I learnt to resent my own mother for doing this. I have now tried to find it in my heart to try and forgive her but it’s extremely hard. I don’t think our relationship could ever be the same.”

She also touched on how female genital mutilation has affected her life and her earliest memories of the effect of FGM she experienced.

“My most vivid memory is how hard and painful it was for me to go to the toilet. It would take me over ten minutes to pee. It burnt so much but at the time I didn’t understand… I would complain to my mum, like ‘mama it hurts when I pee’ and she would just look at me and not say a word. I’ve gotten used to the pain now, but now that I’m older, it all makes sense, and it disgust me, I even feel sick thinking about it, this underground scheme .”

Farah also spoke on how she knows of other family members currently in the UK who will probably go through exactly the same thing as she did.

“As soon as I realised what happened to me, I instantly thought about my other family members in Egypt who have certainly gone through this, but deem it as normal; as opposed to child abuse. I thought of my little sister and immediately felt sick, I thought of my younger cousins too who are all British citizens, and thought of the ‘happy memories’ they’ve had on holiday in Egypt. I instantly connected with other Egyptian females in the UK who have also had FGM done through an anonymous Facebook group chat.”

This might not happen as much in the UK, but that doesn’t mean that parents are taking their daughters to their home countries to go through with the procedure and return like everything is fine. The summer holidays is the perfect time as parents take their daughters overseas during this ‘cutting season’.

In 2015 #EndFGM was introduced by the NHS. It aimed to raise awareness over female genital mutilation, however it is still happening as campaigners urge the UK to still act on this issue, whether it be happening here or overseas.

Farah has become an incredible example to her fellow family members and urges them to reach out to FGM-IS, the female genital mutilation information sharing database. It’s a safeguarding ground that looks out for females with a family history of female genital mutilation. It was launched by the Department Of Health and the NHS.

She ended our interview by asking a question.

“It’s honestly shocking to me how there’s even a possibility for this to happen? How far are we willing to permanently damage our daughters without their consent for something due to our personal credence.”

Female genital mutilation is still very much happening in the UK, whether it be here or anywhere else. British citizens and students are still being flown out to carry out the procedure. Females like Farah are doing everything in their power to prevent young girls like her old self go through anything like that. With research and prevention happening it’s still a cultural, traditional and generational practice that we won’t see the end of for a very long time, but will this operation die out in future generations?

If you have any concerns over female genital mutilation or know anyone who needs help, make sure you reach out to Freedom Charity or Forward Charity who will provide you with help if you or someone you know is at risk of FGM.